Ethiopia (English pronunciation: /ˌiːθiˈoʊpiə/; Amharic: ኢትዮጵያ?, ʾĪtyōṗṗyā, ![]() listen (help·info)), officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa, and is the most populous landlocked country in the world. It is bordered by Eritrea to the north,Djibouti and Somalia to the east, Sudan and South Sudan to the west, and Kenya to the south. Ethiopia is the second-most populous nation on the African continent, with over 84,320,000 inhabitants,[3] and the tenth largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2. Its capital, Addis Ababa, is known as “the political capital of Africa.”

listen (help·info)), officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa, and is the most populous landlocked country in the world. It is bordered by Eritrea to the north,Djibouti and Somalia to the east, Sudan and South Sudan to the west, and Kenya to the south. Ethiopia is the second-most populous nation on the African continent, with over 84,320,000 inhabitants,[3] and the tenth largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2. Its capital, Addis Ababa, is known as “the political capital of Africa.”

Ethiopia is one of the oldest sites of human existence known to scientists.[5] It may be the region from which Homo sapiens first set out for theMiddle East and points beyond.[6][7][8] Ethiopia was a monarchy for most of its history until the last dynasty of Haile Selassie ended in 1974, and theEthiopian dynasty traces its roots to the 2nd century BC.[9] Alongside Rome, Persia, China and India,[10] the Kingdom of Aksum was one of the great world powers of the 3rd century and the first major empire in the world to officially adopt Christianity as a state religion in the 4th century.[11][12][13] During the Scramble for Africa, Ethiopia was the only African country beside Liberia that retained its sovereignty as a recognized independent country, and was one of only four African members of the League of Nations. Ethiopia then became a founding member of the UN. When other African nations received their independence following World War II, many of them adopted the colors of Ethiopia’s flag, and Addis Ababa became the location of several global organizations focused on Africa. Ethiopia is one of the founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement, G-77and the Organisation of African Unity. Addis Ababa is currently the headquarters of the African Union, the Pan African Chamber of Commerce,UNECA and the African Standby Force.

The ancient Ge’ez script is widely used in Ethiopia. The Ethiopian calendar is seven to eight years behind the Gregorian calendar. The country is amultilingual and multiethnic society of around 80 groups, with the two largest being the Oromo and the Amhara, both of which speak Afro-Asiatic languages. The majority of the population is Christian while a third of it is Muslim. Ethiopia is the site of the first Hijra in Islamic history and the oldest Muslim settlement in Africa at Negash. A substantial population of Ethiopian Jews resided in Ethiopia until the 1980s. The country is also the spiritual homeland of the Rastafari movement. There are 9 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Ethiopia.

Despite being the major source of the Nile, Ethiopia underwent a series of famines in the 1980s, exacerbated by adverse geopolitics and civil wars. The country has begun to recover, and it now has the biggest economy by GDP in East Africa and Central Africa.[14][15][16] Ethiopia follows a federal republic political system and EPRDF has been the ruling party since 1991.

Names

The Greek name Αἰθιοπία (from Αἰθίοψ, Aithiops, ‘an Ethiopian’) appears twice in the Iliad and three times in the Odyssey.[17] The Greek historianHerodotus specifically uses it for all the lands south of Egypt,[18] including Sudan and modern Ethiopia. Pliny the Elder says the country’s name comes from a son of Hephaestus (aka Vulcan) named Aethiops.[19] Similarly, in the 15th century Ge’ez Book of Aksum, the name is ascribed to a legendary individual called Ityopp’is, an extrabiblical son of Cush, son of Ham, said to have founded the city of Axum. In addition to this Cushite figure, two of the earliest Semitic kings are also said to have born the name Ityopp’is according to traditional Ethiopian king lists. Modern European scholars beginning c. 1600[20] have considered the name to be derived from the Greek words aitho “I burn” + ops “face”.[21][22]

The name Ethiopia also occurs in many translations of the Old Testament, but the Hebrew texts have Kush, which refers principally to Nubia.[23] In the (Greek) New Testament, however, the Greek term Aithiops, ‘an Ethiopian’, does occur,[24] referring to a servant of Candace or Kentakes, possibly an inhabitant of Meroe which was later conquered and destroyed by the Kingdom of Axum. The earliest attested use of the name Ityopya in the region itself is as a name for the Kingdom of Aksum in the 4th century, in stone inscriptions of King Ezana,[25] who first Christianized the entire apparatus of the kingdom.

In English, and generally outside Ethiopia, the country was also once historically known as Abyssinia, derived from Habesh, an early Arabic form of the Ethiosemitic name “Ḥabaśāt” (unvocalized “ḤBŚT”). The modern form Habesha is the native name for the country’s inhabitants (while the country has been called “Ityopp’ya”). In a few languages, Ethiopia is still referred to by names cognate with “Abyssinia,” e.g., modern Arabic Al-Ḥabashah.

History

Prehistory

It was not until 1963 that evidence of the presence of ancient hominids was discovered in Ethiopia, many years after similar such discoveries had been made in neighbouring Kenya and Tanzania. The discovery was made by Gerrard Dekker, a Dutch hydrologist, who found Acheulian stone tools that were over a million years old at Kella.[1] Since then many important finds have propelled Ethiopia to the forefront of palaentology. The oldest hominid discovered to date in Ethiopia is the 4.2 million year old Ardipithicus ramidus (Ardi) found by Tim D. White in 1994.[2] The most well known hominid discovery is Lucy, found in the Awash Valley of Ethiopia’s Afar region in 1974 by Donald Johanson, and is one of the most complete and best preserved, adult Australopithecinefossils ever uncovered. Lucy’s taxonomic name, Australopithecus afarensis, means ‘southern ape of Afar’, and refers to the Ethiopian region where the discovery was made. Lucy is estimated to have lived 3.2 million years ago.[3] There have been many other notable fossil findings in the country. Near Gona stone tools were uncovered in 1992 that were 2.52 million years old, these are the oldest such tools ever discovered anywhere in the world.[4]In 2010 fossilised animal bones, that were 3.4 million years old, were found with stone-tool-inflicted marks on them in the Lower Awash Valley by an international team, led by Shannon McPherron, which is the oldest evidence of stone tool use ever found anywhere in the world.[5]

East Africa, and more specifically the general area of Ethiopia, is widely considered the site of the emergence of early Homo sapiens in the Middle Paleolithic. In 2004 fossils found near the Omoriver at Kibbish by Richard Leakey in 1967 were redated to 195,000 years old, the oldest date anywhere in the world for modern Homo Sapiens. Homo sapiens idaltu, found in the Middle Awash in Ethiopia in 1997, lived about 160,000 years ago.[6]

Bronze Age contacts with Egypt

The earliest records of Ethiopia appear in Ancient Egypt, during the Old Kingdom period. Egyptian traders from about 3000 BC who refer to lands south of Nubia or Kush as Punt and Yam. The Ancient Egyptians were in possession of myrrh (found in Punt) as early as the First or Second Dynasties, which Richard Pankhurst interprets to indicate trade between the two countries was extant from Ancient Egypt’s beginnings. J. H. Breasted posited that this early trade relationship could have been realized through overland trade down the Nile and its tributaries (i.e. the Blue Nileand Atbara). The Greek historian and geographer Agatharchides had documented seafaring among the early Egyptians: “During the prosperous period of the Old Kingdom, between the 30th and 25th centuries B. C., the river-routes were kept in order, and Egyptian ships sailed the Red Sea as far as the myrrh-country.”[7]

The first known voyage to Punt occurred in the 25th century BC under the reign of Pharaoh Sahure. The most famous expedition to Punt, however, comes during the reign of Queen Hatshepsut probably around 1495 BC, as the expedition was recorded in detailed reliefs on the temple of Deir el-Bahri at Thebes. The inscriptions depict a trading group bringing back myrrh trees, sacks of myrrh, elephant tusks, incense, gold, various fragmented wood, and exotic animals. Detailed information about these two nations is sparse, and there are many theories concerning their locations and the ethnic relationship of their peoples. The Egyptians sometimes called Punt land Ta-Netjeru, meaning “Land of the Gods,” and considered it their place of origin.[8]

Evidence of Naqadan contacts include obsidian from Ethiopia and the Aegean.[9]

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]Dʿmt

There is some confusion over the usage of the word Ethiopia in ancient times and the modern country.

For example, many ancient maps of Africa, which appeared approximately at the time of the European Age of Discovery, named the continent of Africa as Aethiopia, also naming what we now call the Atlantic Ocean, as Oceanus Aethopicus.

Ancient Greeks historians such as Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus used the word Aethiopia (Αιθιοπία) to refer to the peoples living immediately to the south of ancient Egypt, specifically the area now known as the ancient Kingdom of Kush, now a part of modern Nubia in Egypt and Sudan, as well as all of Sub-Saharan Africa in general.

It is now known that in ancient times the name Ethiopia was primarily used to refer to the modern day nation of Sudan based in the upper Nile valley south of Egypt, also called Kush, and then secondarily in reference to Sub-Saharan Africa in general.[10][11][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]Reference to the Kingdom of Aksum designated as Ethiopia dates only as far back as the first half of 4th century following the 4th century invasion of Kush in Sudan by the Aksumite empire. Earlier inscription of Ezana Habashat (the source for “Abyssinia”) in Ge’ez, South Arabian alphabet, was then translated in Greek as “Aethiopia”.

The state of Sheba mentioned in the Old Testament is sometimes believed to have been in Ethiopia, but more often is placed in Yemen. According to the Ethiopian legend, best represented in the Kebra Negest, the Queen of Sheba was tricked by King Solomon into sleeping with him, resulting in a child, named Ebn Melek (later Emperor Menelik I). When he was of age, Menelik returned to Israel to see his father, who sent with him the son of Zadok to accompany him with a replica of the Ark of the Covenant (Ethiosemitic: tabot). On his return with some of the Israelite priests, however, he found that Zadok’s son had stolen the real Ark of the Covenant. Some believe the Ark is still being preserved today at the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Axum, Ethiopia. The tradition that the biblical Queen of Sheba was a ruler of Ethiopia who visited King Solomon in Jerusalem in ancient Israel is supported by the 1st century AD Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, who identified Solomon’s visitor as a queen of Egypt and Ethiopia.

Ethiopia is frequently mentioned in the Bible in English translation based on the Greek translation of “Kush” as “Ethiopia,” however as the Hebrew original references “Kush” such references are in fact to Nubia in the modern day nations of Egypt and Sudan and not the modern-day nation of Ethiopia. An example of this conflation of the nations of Ethiopia and Sudan is in the oft-cited story of the Ethiopian eunuch as written in Acts, Chapter 8, verse 27: “Then the angel of the Lord said to Philip, Start out and go south to the road that leads down from Jerusalem to Gaza. So he set out and was on his way when he caught sight of an Ethiopian. This man was a eunuch, a high official of the Kandake (Candace) Queen of Ethiopia in charge of all her treasure.” The passage continues by describing how Philip helped the Ethiopian understand one passage of Isaiah that the Ethiopian was reading. After the Ethiopian received an explanation of the passage and came to believe in Jesus as the “Son of God”, he requested that Philip baptize him, which Philip obliged. Queen Gersamot Hendeke VII (very similar to Kandake) was the Queen of Ethiopia from the year 42 to 52. However, as the Ethiopian Orthodox Church was founded in the 4th century by Syrian monks, this reference has been shown to be ahistorical. This is because as the original Hebrew uses the word “Kush,” this passage has been more properly identified as referencing the ancient Kingdom of Kush, in Sudan and not Ethiopia, and which in fact was Christianized much earlier than the modern-day nation of Ethiopia. identified in antiquity with Arabia Felix and parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly Nubia in modern-day Sudan.[10][11] Due to secondary English translations of the Bible from Greek instead of Hebrew, which often substitute the word “Cush” (which in Hebrew sometimes means ‘dark’) for “Ethiopia,” (Greek for ‘burnt skin’) there has been some confusion in identifying “Cush” primarily with modern-day Ethiopia, although that is certainly ahistorical.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

[edit]Axum

The first verifiable kingdom of great power to rise in Ethiopia was that of Axum in the 1st century AD. It was one of many successor kingdoms toDʿmt and was able to unite the northern Ethiopian plateau beginning around the 1st century BC. They established bases on the northern highlands of the Ethiopian Plateau and from there expanded southward. The Persian religious figure Mani listed Axum with Rome, Persia, and China as one of the four great powers of his time. The origins of the Axumite Kingdom are unclear, although experts have offered their speculations about it. Even whom should be considered the earliest known king is contested: although C. Conti Rossini proposed that Zoskales of Axum, mentioned in thePeriplus of the Erythraean Sea, should be identified with one Za Haqle mentioned in the Ethiopian King Lists (a view embraced by later historians of Ethiopia such as Yuri M. Kobishchanov[19] and Sergew Hable Sellasie), G.W.B. Huntingford argued that Zoskales was only a sub-king whose authority was limited to Adulis, and that Conti Rossini’s identification can not be substantiated.[20]

Inscriptions have been found in southern Arabia celebrating victories over one GDRT, described as “nagashi of Habashat [i.e. Abyssinia] and of Axum.” Other dated inscriptions are used to determine a floruit for GDRT (interpreted as representing a Ge’ez name such as Gadarat, Gedur, Gadurat or Gedara) around the beginning of the 3rd century. A bronze scepter or wand has been discovered at Atsbi Dera with an inscription mentioning “GDR of Axum”. Coins showing the royal portrait began to be minted under King Endubis toward the end of the 3rd century.

Christianity was introduced into the country by Frumentius, who was consecrated first bishop of Ethiopia by Saint Athanasius of Alexandria about 330. Frumentius converted Ezana, who has left several inscriptions detailing his reign both before and after his conversion. One inscription found at Axum, states that he conquered the nation of the Bogos, and returned thanks to his father, the god Mars, for his victory. Later inscriptions show Ezana’s growing attachment to Christianity, and Ezana’s coins bear this out, shifting from a design with disc and crescent to a design with a cross. Expeditions by Ezana into the Kingdom of Kush at Meroe in Sudan may have brought about its demise, though there is evidence that the kingdom was experiencing a period of decline beforehand. As a result of Ezana’s expansions, Aksum bordered the Roman province of Egypt. The degree of Ezana’s control over Yemen is uncertain. Though there is little evidence supporting Aksumite control of the region at that time, his title, which includes king of Saba and Salhen, Himyar and Dhu-Raydan (all in modern-day Yemen), along with gold Aksumite coins with the inscriptions, “king of the Habshat” or “Habashite,” indicate that Aksum might have retained some legal or actual footing in the area.[21]

Toward the close of the 5th century, a great company of monks known as the Nine Saints are believed to have established themselves in the country. Since that time, monasticism has been a power among the people, and not without its influence on the course of events.

The Axumite Kingdom is recorded once again as controlling part – if not all – of Yemen in the 6th century. Around 523, the Jewish king Dhu Nuwascame to power in Yemen and, announcing that he would kill all the Christians, attacked an Aksumite garrison at Zafar, burning the city’s churches. He then attacked the Christian stronghold of Najran, slaughtering the Christians who would not convert. Emperor Justin I of the Eastern Roman empire requested that his fellow Christian, Kaleb, help fight the Yemenite king, and around 525, Kaleb invaded and defeated Dhu Nuwas, appointing his Christian follower Sumuafa’ Ashawa’ as his viceroy. This dating is tentative, however, as the basis of the year 525 for the invasion is based on the death of the ruler of Yemen at the time, who very well could have been Kaleb’s viceroy. Procopius records that after about five years,Abraha deposed the viceroy and made himself king (Histories 1.20). Despite several attempted invasions across the Red Sea, Kaleb was unable to dislodge Abreha, and acquiesced in the change; this was the last time Ethiopian armies left Africa until the 20th century when several units participated in the Korean War. Eventually Kaleb abdicated in favor of his son Wa’zeb and retired to a monastery, where he ended his days. Abraha later made peace with Kaleb’s successor and recognized his suzerainty. Despite this reverse, under Ezana and Kaleb the kingdom was at its height, benefiting from a large trade, which extended as far as India and Ceylon, and were in constant communication with the Byzantine Empire.

Details of the Axumite Kingdom, never abundant, become even more scarce after this point. The last king known to mint coins is Armah, whose coinage refers to the Persian conquest of Jerusalem in 614. An early Muslim tradition is that the Negus Ashama ibn Abjar offered asylum to a group of Muslims fleeing persecution during Muhammad‘s life (615), but Stuart Munro-Hay believes that Axum had been abandoned as the capital by then[22] – although Kobishchanov states that Ethiopian raiders plagued the Red Sea, preying on Arabian ports at least as late as 702.[23]

Some people believed the end of the Axumite Kingdom is as much of a mystery as its beginning. Lacking a detailed history, the kingdom’s fall has been attributed to a persistent drought, overgrazing, deforestation, plague, a shift in trade routes that reduced the importance of the Red Sea—or a combination of these factors. Munro-Hay cites the Muslim historian Abu Ja’far al-Khwarazmi/Kharazmi (who wrote before 833) as stating that the capital of “the kingdom of Habash” was Jarma. Unless Jarma is a nickname for Axum (hypothetically from Ge’ez girma, “remarkable, revered”), the capital had moved from Axum to a new site, yet undiscovered.[24]

[edit]Middle Ages

Zagwe dynasty

About 1000 (presumably c 960), a non-Christian princess, Yodit (“Gudit”, a play on Yodit meaning evil), conspired to murder all the members of the royal family and establish herself as monarch. According to legends, during the execution of the royals, an infant heir of the Axumite monarch was carted off by some faithful adherents, and conveyed to Shewa, where his authority was acknowledged, while Yodit reigned for forty years over the rest of the kingdom, and transmitted the crown to her descendants. At one point during the next century, the last of Yodit’s successors were overthrown by anAgaw lord named Mara Takla Haymanot, who founded the Zagwe dynasty and married a female descendant of the Axumite monarchs (“son-in-law”) or previous ruler.

[edit]Ethiopia and the Crusades

Although Medieval Ethiopia was very isolated from the other Christian Nations, they did maintain a degree of contact through Jerusalem. Like many other nations and denominations, the Ethiopian Church maintained a series of small chapels and even an annex at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[25]Saladin, after retaking the Holy City in 1187, expressly invited the Ethiopian monks to return and even exempted Ethiopian pilgrims from the pilgrim tax. His two edicts provide evidence of Ethiopia’s contact with these Crusader States during this period.[26] It was during this period that the great Ethiopian king Gebre Mesqel Lalibela ordered the construction of the legendary rock-hewn churches of Lalibela.

Later, as the Crusades were dying out in the early fourteenth century, the Ethiopian King Wedem Ar’ad dispatched a thirty man mission to Europe, where they traveled to Rome to meet the Pope and then, since the Medieval Papacy was in schism, they traveled to Avignon to meet the Antipope. During this trip, the Ethiopian mission also traveled to France, Spain and Portugal in the hopes of building an alliance against the Muslim states then threatening Ethiopia’s existence. Plans were even drawn up of a two-pronged invasion of Egypt with the French King, but nothing ever came of the talks, although this brought Ethiopia back to Europe’s attention, leading to expansion of European influence when the Portuguese explorers reached the Indian Ocean.[27]

[edit]Early Solomonic period (1270-1529)

Around 1270, a new dynasty was established in the Abyssinian highlands under Yekuno Amlak who deposed the last of the Zagwe kings and married one of his daughters. According to legends, the new dynasty were male-line descendants of Axumite monarchs, now recognized as the continuingSolomonic dynasty (the kingdom being thus restored to the biblical royal house).

Under the Solomonic dynasty, the chief provinces became Tigray (northern), Amhara (central) and Shewa (southern). The seat of government, or rather of overlordship, had usually been in Amhara or Shewa, the ruler of which, calling himself nəgusä nägäst, exacted tribute, when he could, from the other provinces. The title of nəgusä nägäst was to a considerable extent based on their alleged direct descent from Solomon and the queen of Sheba; but it is needless to say that in many, if not in most, cases their success was due more to the force of their arms than to the purity of their lineage.

[edit]Portuguese influence

Towards the close of the 15th century the Portuguese missions into Ethiopia began. A belief had long prevailed in Europe of the existence of a Christian kingdom in the far east, whose monarch was known as Prester John, and various expeditions had been sent in quest of it. Among others engaged in this search was Pêro da Covilhã, who arrived in Ethiopia in 1490, and, believing that he had at length reached the far-famed kingdom, presented to thenəgusä nägäst of the country, a letter from his master the king of Portugal, addressed to Prester John.

Pêro da Covilhã remained in the country, but in 1507 an Armenian named Matthew was sent by the Emperor to the king of Portugal to request his aid against the Muslims. In 1520 a Portuguese fleet, with Matthew on board, entered the Red Sea in compliance with this request, and an embassy from the fleet visited the Emperor, Lebna Dengel, and remained in Ethiopia for about six years. One of this embassy was Father Francisco Álvares, who wrote one of the earliest accounts of the country.[28]

[edit]The Abyssinian-Adal War (1529-1543)

Between 1528 and 1540 armies of Muslims, under the Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi, entered Ethiopia from the low country to the south-east, and overran the kingdom, obliging the emperor to take refuge in the mountain fastnesses. In this extremity recourse was again had to the Portuguese. João Bermudes, a subordinate member of the mission of 1520, who had remained in the country after the departure of the embassy, was, according to his own statement (which is untrustworthy), ordained successor to the Abuna (archbishop), and sent to Lisbon. Bermudes certainly came to Europe, but with what credentials is not known.

In response to Bermudes message, a Portuguese fleet under the command of Estêvão da Gama, was sent from India and arrived at Massawa in February 1541. Here he received an ambassador from the Emperor beseeching him to send help against the Muslims, and in the July following a force of 400 musketeers, under the command of Cristóvão da Gama, younger brother of the admiral, marched into the interior, and being joined by native troops were at first successful against the enemy; but they were subsequently defeated at the Battle of Wofla (28 August 1542), and their commander captured and executed. On February 21, 1543, however, Ahmad was shot and killed in the Battle of Wayna Daga and his forces totally routed. After this, quarrels arose between the Emperor and Bermudes, who had returned to Ethiopia with Gama and now urged the emperor to publicly profess his obedience to Rome. This the Emperor refused to do, and at length Bermudes was obliged to make his way out of the country.[28]

[edit]Early Gondar period (1632-1769)

The Jesuits who had accompanied or followed the Gama expedition into Ethiopia, and fixed their headquarters at Fremona (near Adwa), were oppressed and neglected, but not actually expelled. In the beginning of the 17th century Father Pedro Páez arrived at Fremona, a man of great tact and judgment, who soon rose into high favour at court, and won over the emperor to his faith. He directed the erection of churches, palaces and bridges in different parts of the country, and carried out many useful works. His successor Afonso Mendes was less tactful, and excited the feelings of the people against him and his fellow Europeans, until upon the death of Emperor Susenyos and the accession of his son Fasilides in 1633, the Jesuits were expelled and the native religion restored to official status. Fasilides made Gondar his capital and built a castle there which would grow into the castle complex known as the Fasil Ghebbi, or Royal Enclosure. Fasilides also constructed several churches in Gondar, many bridges across the country, and expanded theChurch of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Aksum.

During this time of religious strife Ethiopian philosophy flourished, and it was during this period that the philosophers Zera Yacob and Walda Heywatlived. Zera Yaqob is known for his treatise on religion, morality, and reason, known as Hatata.[29]

[edit]Aussa Sultanate

The Aussa Sultanate or Afar Sultanate succeeded the earlier Imamate of Aussa. The latter polity had come into existence in 1577, when Muhammed Jasamoved his capital from Harar to Aussa with the split of the Adal Sultanate into Aussa and the Harari city-state. At some point after 1672, Aussa declined and temporarily came to an end in conjunction with Imam Umar Din bin Adam‘s recorded ascension to the throne.[30]

The Sultanate was subsequently re-established by Kedafu around the year 1734, and was thereafter ruled by his Mudaito Dynasty.[31] The primary symbol of the Sultan was a silver baton, which was considered to have magical properties.[32]

[edit]Zemene Mesafint

This era was, on one hand, a religious conflict between settling Muslims and traditional Christians, between nationalities they represented, and on the other hand between feudal lords on power over the central government.

Some historians date the murder of Iyasu I, and the resultant decline in the prestige of the dynasty, as the beginning of the Ethiopian Zemene Mesafint (“Era of the Princes”), a time of disorder when the power of the monarchy was eclipsed by the power of local warlords.

Nobles came to abuse their positions by making emperors, and encroached upon the succession of the dynasty, by candidates among the nobility itself: e.g. on the death of Emperor Tewoflos, the chief nobles of Ethiopia feared that the cycle of vengeance that had characterized the reigns of Tewoflos and Tekle Haymanot I would continue if a member of the Solomonic dynasty were picked for the throne, so they selected one of their own,Yostos to be negusa nagast (king of kings) – however his tenure was brief.

Iyasu II ascended the throne as a child. His mother, Empress Mentewab played a major role in Iyasu’s reign, as well as in that of her grandson Iyoastoo. Mentewab had herself crowned as co-ruler, becoming the first woman to be crowned in this manner in Ethiopian history.

Empress Mentewab was crowned co-ruler upon the succession of her son (a first for a woman in Ethiopia) in 1730, and held unprecedented power over government during his reign. Her attempt to continue in this role following the death of her son 1755 led her into conflict with Wubit (Welete Bersabe), his widow, who believed that it was her turn to preside at the court of her own son Iyoas. The conflict between these two queens led to Mentewab summoning her Kwaran relatives and their forces to Gondar to support her. Wubit responded by summoning her own Oromo relatives and their considerable forces from Yejju.

The treasure of the Empire being allegedly penniless on the death of Iyasu, it suffered further from ethnic conflict between nationalities that been part of the Empire for hundreds of years—the Agaw, Amharans, Showans, and Tigreans — and the Oromo newcomers. Mentewab’s attempt to strengthen ties between the monarchy and the Oromo by arranging the marriage of her son to the daughter of an Oromo chieftain backfired in the long run. Iyasu II gave precedence to his mother and allowed her every prerogative as a crowned co-ruler, while his wife Wubit suffered in obscurity. Wubit waited for the accession of her own son to make a bid for the power wielded for so long by Mentewab and her relatives from Qwara. When Iyoas assumed the throne upon his father’s sudden death, the aristocrats of Gondar were stunned to find that he more readily spoke in the Oromo language rather than in Amharic, and tended to favor his mother’s Yejju relatives over the Qwarans of his grandmothers family. Iyoas further increased the favor given to the Oromo when adult. On the death of the Ras of Amhara, he attempted to promote his uncle Lubo governor of that province, but the outcry led his advisor Wolde Leul to convince him to change his mind.

It is believed that the power struggle between the Qwarans led by the Empress Mentewab, and the Yejju Oromos led by the Emperor’s mother Wubit was about to erupt into an armed conflict. RasMikael Sehul was summoned to mediate between the two camps. He arrived and shrewdly maneuvered to sideline the two queens and their supporters making a bid for power for himself. Mikael settled soon as the leader of Amharic-Tigrean (Christian) camp of the struggle.

The reign of Iyaos’ reign becomes a narrative of the struggle between the powerful Ras Mikael Sehul and the Oromo relatives of Iyoas. As Iyoas increasingly favored Oromo leaders like Fasil, his relations with Mikael Sehul deteriorated. Eventually Mikael Sehul deposed the Emperor Iyoas (7 May 1769). One week later, Mikael Sehul had him killed; although the details of his death are contradictory, the result was clear: for the first time an Emperor had lost his throne in a means other than his own natural death, death in battle, or voluntary abdication.

Mikael Sehul had compromised the power of the Emperor, and from this point forward it lay ever more openly in the hands of the great nobles and military commanders. This point of time has been regarded as one start of the Era of the Princes.

An aged and infirm imperial uncle prince was enthroned as Emperor Yohannes II. Ras Mikael soon had him murdered, and underage Tekle Haymanot IIwas elevated to the throne.

This bitter religious conflict contributed to hostility toward foreign Christians and Europeans, which persisted into the 20th century and was a factor in Ethiopia’s isolation until the mid-19th century, when the first British mission, sent in 1805 to conclude an alliance with Ethiopia and obtain a port on the Red Sea in case France conquered Egypt. The success of this mission opened Ethiopia to many more travellers, missionaries and merchants of all countries, and the stream of Europeans continued until well into Tewodros‘s reign.

This isolation was pierced by very few European travellers. One was the French physician C.J. Poncet, who went there in 1698, via Sennar and the Blue Nile. After him James Bruce entered the country in 1769, with the object of discovering the sources of the Nile, which he was convinced lay in Ethiopia. Accordingly, leaving Massawa in September 1769, he travelled via Axum to Gondar, where he was well received by Emperor Tekle Haymanot II. He accompanied the king on a warlike expedition round Lake Tana, moving South round the eastern shore, crossing the Blue Nile (Abay) close to its point of issue from the lake and returning via the western shore. Bruce subsequently returned to Egypt at the end of 1772 by way of the upper Atbara, through the kingdom of Sennar, the Nile, and the Korosko desert. During the 18th century the most prominent rulers were the emperor Dawit III of Gondar (died May 18, 1721), Amha Iyasus of Shewa), who consolidated his kingdom and founded Ankober, and Tekle Giyorgis of Amhara) – the last-mentioned is famous of having been elevated to the throne altogether six times and also deposed six times. The first years of the 19th century were disturbed by fierce campaigns between Ras Gugsa of Begemder, and Ras Wolde Selassie of Tigray, who fought over control of the figurehead Emperor Egwale Seyon. Wolde Selassie was eventually the victor, and practically ruled the whole country till his death in 1816 at the age of eighty.

Dejazmach Sabagadis of Agame succeeded Wolde Selassie in 1817, through force of arms, to become warlord of Tigre.

[edit]Modern

[edit]1855-1936

Under the Emperors Tewodros II (1855–1868), Yohannes IV (1872–1889), and Menelek II (1889–1913), the empire began to emerge from its isolation. Under Emperor Tewodros II, the “Age of the Princes” (Zemene Mesafint) was brought to an end.

[edit]Tewodros II and Tekle Giyorgis II (1855-1872)

On February 11, 1855, Kassa deposed the last of the Gondarine puppet Emperors, and was crownednegusa nagast of Ethiopia under the name of Tewodros II. He soon after advanced against Shewa with a large army. Chief of the notables opposing him was its king Haile Melekot, a descendant ofMeridazmach Asfa Wossen. Dissensions broke out among the Shewans, and after a desperate and futile attack on Tewodros at Dabra Berhan, Haile Melekot died of illness, nominating with his last breath his eleven-year-old son as successor (November 1855) under the name Negus Sahle Maryam (the future emperor Menelek II). Darge, Haile Melekot’s brother, and Ato Bezabih, a Shewan noble, took charge of the young prince, but after a hard fight with Angeda, the Shewans were obliged to capitulate. Sahle Maryam was handed over to the Emperor, taken to Gondar, and there trained in Tewodros’s service, and then placed in comfortable detention at the fortress of Magdala. Tewodoros afterwards devoted himself to modernizing and centralizing the legal and administrative structure of his kingdom, against the resistance of his governors. Sahle Maryam of Shewa was married to Tewodros II’s daughter Alitash.

In 1865, Sahle Maryam escaped from Maqdala, abandoning his wife, and arrived in Shewa, and was there acclaimed as Negus. Tewodros forged an alliance between Britain and Ethiopia, but as explained in the next section, he committed suicide after a military defeat by the British. On the death of Tewodros, many Shewans, including Ras Darge, were released, and the young Negus of Shewa began to feel himself strong enough, after a few preliminary minor campaigns, to undertake offensive operations against the northern princes. But these projects were of little avail, for Ras Kassai of Tigray, had by this time (1872) risen to supreme power in the north. Proclaiming himself negusa nagast under the name of Yohannes (or John) IV, he forced Sahle Maryam to acknowledge his overlordship.

In early 1868, the British force seeking Tewodros’ surrender, after he refused to release imprisoned British subjects, arrived on the coast of Massawa. The British and Dajazmach Kassa came to an agreement in which Kassa would let the British pass through Tigray (the British were going to Magdala which Tewodros had made his capital) in exchange for money and weapons. Surely enough, when the British completed their mission and were leaving the country, they rewarded Kassa for his cooperation with artillery, muskets, rifles, and munitions, all in all worth approximately £500,000 (Marcus 2002, 71-72). This formidable gift came in handy when in July 1871 the current emperor, Emperor Tekle Giyorgis II, attacked Kassa at his capital in Adwa, for Kassa had refused to be named a ras or pay tribute (Marcus, H. 2002, 72). Although Kassa’s army was outnumbered 12,000 to the emperor’s 60,000, Kassa’s army was equipped with more modern weapons and better trained. At battle’s end, forty percent of the emperor’s men had been captured. The emperor was imprisoned and would die a year later. Six months later on 21 January 1872, Kassa became the new emperor under the name Yohannes IV (Zewde, B. 2001, 43).

[edit]Yohannes IV (1872-1889)

Ethiopia was not colonized by a European power until 1936 (see below); however, several colonial powers had interests and designs on Ethiopia in the context of the 19th century “Scramble for Africa.”

When Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom, in 1867 failed to answer a letter Tewodros II of Ethiopia had sent her, he took it as an insult and imprisoned several British residents, including the consul. An army of 12,000 was sent from Bombay to Ethiopia to rescue the captured nationals, under the command of Sir Robert Napier. The Ethiopians were defeated, and the British stormed the fortress of Magdala (now known as Amba Mariam) on April 13, 1868. When the Emperor heard that the gate had fallen, he fired a pistol into his mouth and killed himself. Sir Robert Napier was raised to the peerage, and given the title of Lord Napier of Magdala.

The Italians now came on the scene. Asseb, a port near the southern entrance of the Red Sea, had been bought from the local sultan in March 1870 by an Italian company, which, after acquiring more land in 1879 and 1880, was bought out by the Italian government in 1882. In this year Count Pietro Antonelliwas dispatched to Shewa in order to improve the prospects of the colony by treaties with Sahle Maryam of Shewa and the sultan of Aussa.

In April 1888 the Italian forces, numbering over 20,000 men, came in contact with the Ethiopian army, but negotiations took the place of fighting, with the result that both forces retired, the Italians only leaving some 5,000 troops in Eritrea, later to become an Italian colony.

Meanwhile the Emperor Yohannes IV had been engaged with the dervishes, who had in the meantime become masters of the Egyptian Sudan, and in 1887 a great battle ensued at Gallabat, in which the dervishes, under Zeki Tumal, were beaten. But a stray bullet struck the king, and the Ethiopians decided to retire. The king died during the night, and his body fell into the hands of the enemy (March 9, 1889). When the news of Yohannes’s death reached Sahle Maryam of Shewa, he proclaimed himself emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia, and received the submission of Begemder, Gojjam, the Yejju Oromo, and Tigray.

[edit]Menelik II (1889-1913)

On May 2 of that same year, Emperor Menelik signed the Treaty of Wuchale with the Italians, granting them a portion of Northern Ethiopia, the area that would later be Eritrea and part of the province of Tigray in return for the promise of 30,000 rifles, ammunition, and cannons.[33] The Italians notified the European powers that this treaty gave them a protectorate over all of Ethiopia. Menelik protested, showing that the Amharic version of the treaty said no such thing, but his protests were ignored.

On March 1, 1896, Ethiopia’s conflict with the Italians, the First Italo–Ethiopian War, was resolved by the complete defeat of the Italian armed forces at the Battle of Adowa. A provisional treaty of peace was concluded at Addis Ababa on October 26, 1896, which acknowledged the independence of Ethiopia.

Regarding the question of railways, the first concession for a railway from the coast at Djibouti (French Somaliland) to the interior was granted by Menelik, to a French company in 1894. The railway was completed to Dire Dawa, 28 miles (45 km) from Harrar, by the last day of 1902.

[edit]Iyasu V, Zauditu and Haile Selassie (1913-1936)

When Menelik II died, his grandson, Lij Iyassu, succeeded to the throne but soon lost support because of his Muslim ties. He was deposed in 1916 by the Christian nobility, and Menelik’s daughter, Zauditu, was made empress. Her cousin, Ras Tafari Makonnen, was made regent and successor to the throne.

Upon the death of Empress Zauditu in 1930, Ras Tafari Makonnen, adopting the throne name Haile Selassie, was crowned Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia. His full title was “His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, King of Kings of Ethiopia and Elect of God.”

Following the death of Abba Jifar II of Jimma, Emperor Haile Selassie seized the opportunity to annex Jimma. In 1932, the Kingdom of Jimma was formally absorbed into Ethiopia. During the reorganization of the provinces in 1942, Jimma vanished into Kaffa Province.

[edit]Italian period (1936-1941)

Emperor Haile Selassie’s reign was interrupted in 1935 when Italian forces invaded and occupied Ethiopia.

The Italian army, under the direction of dictator Benito Mussolini, invaded Ethiopian territory on October 2, 1935. They occupied the capital Addis Ababa on May 5. Emperor Haile Selassie pleaded to the League of Nations for aid in resisting the Italians. Nevertheless the country was formally annexed on May 9, 1936 and the Emperor went into exile.

The war was full of cruelty: the Ethiopians used Dum-dum bullets (prohibited by the Hague Convention of 1899, Declaration III) and the Italians used gas (prohibited under the Geneva Protocol of 1922).[34] Many Ethiopians died in the invasion. The Negus claimed that more than 275,000 Ethiopian fighters were killed compared to only 1,537 Italians, while the Italian authorities estimated that 16,000 Ethiopians and 2,700 Italians (including Italian colonial troops) died in battle.[35]

Italy in 1936 requested the League of Nations to recognize the annexation of Ethiopia: all member nations (including Britain and France), with the exception of the Soviet Union, voted to support it. The King of Italy (Victor Emmanuel III) was crowned Emperor of Ethiopia and the Italians created an Italian empire in Africa (Italian East Africa) with Ethiopia, Eritrea and Italian Somalia. In 1937 Mussolini boasted that, with his conquest of Ethiopia, “finally Adua was avenged” and that he had abolished slavery in Ethiopia.[36]

The Italians invested substantively in Ethiopian infrastructure development. They created the “imperial road” between Addis Abeba and Massaua, the Addis Abeba – Mogadishu and the Addis Abeba – Assab.[37] 900 km of railways were reconstructed or initiated (like the railway between Addis Abeba and Assab), dams and hydroelectric plants were built, and many public and private companies were established in the underdeveloped country. The most important were: “Compagnie per il cotone d’Etiopia” (Cotton industry); “Cementerie d’Etiopia” (Cement industry); “Compagnia etiopica mineraria” (Minerals industry); “Imprese elettriche d’Etiopia” (Electricity industry); “Compagnia etiopica degli esplosivi” (Armament industry); “Trasporti automobilistici (Citao)” (Mechanic & Transport industry).

Much of these improvements were part of a plan to bring half a million Italians to colonize the Ethiopian plateaus. In October 1939 the Italian colonists in Ethiopia were 35,441, of whom 30,232 male (85.3%) and 5,209 female (14.7%), most of them living in urban areas.[38] Only 3,200 Italian farmers moved to colonize farm areas, where they were under sporadic attack by pro-Haile Selassie guerrillas.

[edit]World War II

In spring 1941 the Italians were defeated by British and Allied forces (including Ethiopian forces). On May 5, 1941, Emperor Haile Selassie re-entered Addis Ababa and returned to the throne. The Italians, after their final stand at Gondar in November 1941, conducted a guerrilla war in Ethiopia, that lasted until summer 1943. After the surrender of Italy, Ethiopia annexed the former Italian colony of Eritrea.

[edit]Post–World War II period (1941-1974)

After World War II, Emperor Haile Selassie exerted numerous efforts to promote the modernization of his nation. The country’s first important school of higher education, University College of Addis Ababa, was founded in 1950. The Constitution of 1931 was replaced with the 1955 constitution which expanded the powers of the Parliament. While improving diplomatic ties with the United States, Haile Selassie also sought to improve the nation’s relationship with other African nations. To do this, in 1963, he helped to found theOrganisation of African Unity.

In 1961 the 30-year Eritrean Struggle for Independence began, following the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I‘s dissolution of the federation and shutting down the Eritrean parliament. The Emperor declared Eritrea the fourteenth province of Ethiopia in 1962.[39] The Negus suffered criticism due to the expenses involved in fighting the Nationalist forces.

By the early 1970s Emperor Haile Selassie’s advanced age was becoming apparent. As Paul B. Henze explains: “Most Ethiopians thought in terms of personalities, not ideology, and out of long habit still looked to Haile Selassie as the initiator of change, the source of status and privilege, and the arbiter of demands for resources and attention among competing groups.”[40] The nature of the succession, and of the desirability of the Imperial monarchy in general, were in dispute amongst the Ethiopian people.

Perceptions of this war as imperialist were among the primary causes of the growing Ethiopian Marxist movement. In the early 1970s, the Ethiopian Communists received the support of the Soviet Union under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev. This help lead to the 1974 marxist coup of Mengistu.

The government’s failure to effect significant economic and political reforms over the previous fourteen years created a climate of unrest. Combined with rising inflation, corruption, a famine that affected several provinces (especially Welo and Tigray) but was concealed from the outside world, and the growing discontent of urban interest groups, the country was ripe for revolution. The unrest that began in January 1974 became an outburst of general discontent. The Ethiopian military, with assistance from the Comintern, began to both organize and incite a full-fledged revolution.[41]

[edit]Communist period (1974-1991)

After a period of civil unrest which began in February 1974, the aging Emperor Haile Selassie I was removed from his position. On September 12, 1974, a provisional administrative council of soldiers, known as the Derg (“committee”) seized power from the emperor and installed a government which was socialist in name and military in style. The Derg summarily executed 59 members of the former government, including two former Prime Ministers and Crown Councilors, Court officials, ministers, and generals. Emperor Haile Selassie died on August 22, 1975. He was allegedly strangled in the basement of his palace or smothered with a wet pillow.[42]

Lt. Col. Mengistu Haile Mariam assumed power as head of state and Derg chairman, after having his two predecessors killed, as well as tens of thousands of other suspected opponents. The new Marxist government undertook socialist reforms, including nationalisation of landlords’ property[43] and the church’s property. Before the coup, Ethiopian peasants’ way of life was thoroughly influenced by the church teachings; 280 days a year are religious feasts or days of rest. Mengistu’s years in office were marked by a totalitarian-style government and the country’s massive militarization, financed by the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, and assisted by Cuba. In December 1976, an Ethiopian delegation in Moscow signed a military assistance agreement with the Soviet Union. The following April 1977, Ethiopia abrogated its military assistance agreement with the United States and expelled the American military missions.

The new regime in Ethiopia met with armed resistance from the large landowners, the royalists and the nobility.[43] The center of resistance was largely centered in the province of Eritrea.[44] The Derg decided in November 1974 to prosecute war in Eritrea rather than seek a negotiated settlement. By mid-1976, the resistance had gained control of most of the town and the countryside of Eritrea.[45]

In July 1977, sensing the disarray in Ethiopia, Somalia attacked across the Ogaden in pursuit of its irredentist claims to the ethnic Somali areas of Ethiopia (see Ogaden War).[46] They were assisted in this invasion by the armed Western Somali Liberation Front. Ethiopian forces were driven back far inside their own frontiers but, with the assistance of a massive Soviet airlift of arms and 17,000 Cuban combat forces, they stemmed the attack.[47] The last major Somali regular units left the Ogaden March 15, 1978. Twenty years later, the Somali region of Ethiopia remains under-developed and insecure.

From 1977 through early 1978, thousands of suspected enemies of the Derg were tortured and/or killed in a purge called the “Red Terror“. Communism was officially adopted during the late 1970s and early 1980s; in 1984, the Workers’ Party of Ethiopia (WPE) was established, and on February 1, 1987, a new Soviet-style civilian constitution was submitted to a popular referendum. It was officially endorsed by 81% of voters, and in accordance with this new constitution, the country was renamed the People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia on September 10, 1987, and Mengistu became president.

The regime’s collapse was hastened by droughts and famine, which affected around 8 million people, leaving 1 million dead, as well as by insurrections, particularly in the northern regions of Tigray and Eritrea. The regime also conducted a brutal campaign of resettlement and villagization in Ethiopia in the 1980s. In 1989, the Tigrayan Peoples’ Liberation Front (TPLF) merged with other ethnically based opposition movements to form the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). In May 1991, EPRDF forces advanced on Addis Ababa. Mengistu fled the country to asylum in Zimbabwe, where he still resides.

Hundreds of thousands were killed due to the Red Terror, forced deportations, or from using hunger as a weapon.[48] In 2006, after a long trial, Mengistu was found guilty of genocide.[49]

[edit]The Federal Democratic Republic (1991-present)

In July 1991, the EPRDF, the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), and others established the Transitional Government of Ethiopia (TGE) which was composed of an 87-member Council of Representatives and guided by a national charter that functioned as a transitional constitution. In June 1992, the OLF withdrew from the government; in March 1993, members of the Southern Ethiopia Peoples’ Democratic Coalition also left the government.

Eritrea separated from Ethiopia following the fall of the Derg in 1991, after a long independentist war.

In 1994, a new constitution was written that formed a bicameral legislature and a judicial system. An election took place in May 1995 in which Meles Zenawi was elected the Prime Minister and Negasso Gidada was elected President. Also at this time, the members of the Parliament were elected. Ethiopia’s second multiparty election was held in May 2000. Prime Minister Meles was one again elected as Prime Minister in October 2000. In October 2001, Lieutenant Girma Wolde-Giorgis was elected president.

In 2005, during the general elections in Ethiopia, allegations of irregularities that brought victory to the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front resulted in widespread protests in which the government is accused of massacring civilians (see Ethiopian police massacres).

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, and with the rise of radical Islamism, Ethiopia again turned to the Western powers for alliance and assistance. After the September 11 attacks in 2001, the Ethiopian army began to train with US forces based out of the Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa(CJTF-HOA) established in Djibouti, in counterterrorism and counterinsurgency. Ethiopia allowed the US to station military advisors at Camp Hurso.[50]

In 2006, an Islamic organisation seen by many as having ties with al-Qaeda, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), spread rapidly in Somalia. Ethiopia sent logistical support to the Transitional Federal Government opposing the Islamists. Finally, on December 20, 2006, active fighting broke out between the ICU and Ethiopian Army. As the Islamist forces were of no match against the Ethiopian regular army, they decided to retreat and merge among the civilians, and most of the ICU-held Somalia was quickly taken. Human Rights Watch accused Ethiopia of various abuses including indiscriminate killing of civilians during the 2007 battle in Mogadishu. Ethiopian forces pulled out of Somalia in January 2009, leaving a small African Union force and smaller Somali Transitional Government force to maintain the peace. Reports immediately emerged of religious fundamentalist forces occupying one of two former Ethiopian bases in Mogadishu shortly after withdrawal.[51]

Further reading

- African Zion, the Sacred Art of Ethiopia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

- Antonicelli, Franco (1961). Trent’anni di storia italiana 1915 – 1945. Torino: Mondadori.

- Bahru Zewde. A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855-1974, Addis Ababa University Press, Addis Ababa 1991.

- Bernand, Étienne; Drewes, Abraham Johannes; Schneider,Roger; Anfray,Francis (1991). Recueil des inscriptions de l’Ethiopie des périodes pré-axoumite et axoumite. Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, De Boccard. ASIN B0000EAFWP.

- Del Boca, Angelo (1985). Italiani in Africa Orientale: La conquista dell’Impero. Roma: Laterza. ISBN 88-420-2715-4.

- Gibbons, Ann. The First Human : The Race to Discover our Earliest Ancestor. Anchor Books (2007). ISBN 978-1-4000-7696-3

- Henze, Paul B. (2000). A History of Ethiopia. Layers of Time. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-393-3.

- Johanson, Donald & Wong, Kate. Lucy’s Legacy : The Quest for Human Origins. Three Rivers Press (2009). ISBN 978-0-307-39640-2

- Markakis, John & Nega Ayele (1978). Class and Revolution in Ethiopia. Addis Abeba: Shama Books. ISBN 99944-0-008-8.

- Marcus, Harold A History of Ethiopia, Berkeley 1994.

- Mauri, Arnaldo (2003), The Early Development of Banking in Ethiopia, “International Review of Economics”, Vol. 50, n. 4, pp. 521–543.

- Mauri, Arnaldo (2009), The re-establishment of the national monetary and banking system in Ethiopia, 1941-1960, South African Journal of Economic History, Vol. 24, n. 2, pp. 82–130.

- Mauri, Arnaldo “Monetary Developments and Decolonization in Ethiopia”, Acta Universitatis Danubius OEconomica, Vol. 6 n. 1, 2010, pp. 5–15.[2]

- Munro-Hay,Stuart (1992). Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-0209-7.

- Pankhurst, Richard (2001). The Ethiopians: A History (Peoples of Africa). Wiley-Blackwell; New Ed edition. ISBN 0-631-22493-9.

- Pankhurst, Richard (2005). Historic images of Ethiopia. Addis Abeba: Shama books. ISBN 99944-0-015-0.

- Phillipson, David W. (2003). Aksum: an archaeological introduction and guide. Nairobi: The British Institute in Eastern Africa. ISBN 1-872566-19-7.

- Sergew Hable Selassie. Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270 Addis Ababa: United Printers, 1972.

- Taddesse Tamrat. Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527 Hollywood, CA: Tsehai Publishers & Distributors, second printing with new preface and new foreword 2009.

- Vestal, Theodor M. “Consequences of the British occupation of Ethiopia during World War II”, B.J. Ward (ed), Rediscovering the British Empire, Melbourne 2007.

- Young, John (1993). Peasant Revolution in Ethiopia: The Tigray People’s Liberation Front, 1975-1991. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59198-8.

[edit]References

- ^http://geoserver.itc.nl/melkakunture/research/index.html

- ^ Ansari, Azadeh (October 7, 2009). “Oldest human skeleton offers new clues to evolution”.CNN.com/technology. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^“Mother of man – 3.2 million years ago”. Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^http://www.archaeology.org/9703/newsbriefs/tools.html

- ^http://www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/news/2010/august/oldest-tool-use-and-meat-eating-revealed75831.html

- ^ White, Tim D., Asfaw, B., DeGusta, D., Gilbert, H., Richards, G.D., Suwa, G. and Howell, F.C. (2003). “Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia”. Nature423 (6491): 742–747. doi:10.1038/nature01669. PMID12802332.

- ^Agatharchides, in Wilfred Harvey Schoff (Secretary of the Commercial Museum of Philadelphia) with a foreword by W. P. Wilson, Sc. Director, The Philadelphia Museums.Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century, Translated from the Greek and Annotated (1912). New York, New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., pages 50 (for attribution) and 57 (for quote).

- ^ Richard Pankhurst, The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to The End of the 18th century (Asmara: Red Sea Press, Inc., 1997), pp.5, 7, 9.

- ^ Laurent Bavay, Thierry de Putter, Barbara Adams, Jacques Novez, Luc André, 2000. The Origin of Obsidian in Predynastic and Early Dynastic Upper Egypt, MDAIK 56 (2000), pp. 5-20. See on-line post: [1].

- ^ ab Richard Lobban, Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia, Scarecrow Press, 2004. p.1-1i

- ^ abcd David M. Goldenberg, The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, p. 18.

- ^ ab Noah Webster, The Holy Bible: Containing the Old and New Testaments, in the Common Version, p. xiv

- ^ ab Reilly, W. (1908). Cush. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved April 19, 2012 from New Advent:http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04575c.htm

- ^ ab Rodney Steven Sadler, Can a Cushite Change His Skin?: An Examination of Race, Ethnicity, And Othering in the Hebrew Bible.

- ^ abhttp://concordances.org/hebrew/3568.htm

- ^ abwww.jbq.jewishbible.org/assets/Uploads/293/293_Sheba2.pdf

- ^ abhttp://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/5890-ethiopia

- ^ abhttp://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/4815-cush

- ^ Yuri M. Kobishchanov, Axum, Joseph W. Michels, editor; Lorraine T. Kapitanoff, translator, (University Park, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania, 1979), pp.54-59.

- ^ Expressed, for example, in his The Historical Geography of Ethiopia (London: the British Academy, 1989), p.39.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum, p. 81.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum, p.56.

- ^ Kobishchanov, Axum, p.116.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum, pp.95-98.

- ^ Erlich, Haggai. The Cross and the River; Ethiopia, Egypt and the Nile. Boulder: Lynne Rienne Publishers, 2002. p.41-43

- ^ Erlich, p. 37.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard. The Ethiopians, A History. Malden: Blackwell Publishers, Inc, 1998. p.77-85.

- ^ ab Baynes, Thomas Spencer (1838). “Abyssinia”. The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature, Volume 1 (Ninth ed.). Henry G. Allen and Company. p. 65.

- ^ Kiros, Teodoros. “The Meditations of Zara Yaquob”. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ Abir, p. 23 n.1.

- ^ Abir, pp. 23-26.

- ^ Trimingham, p. 262.

- ^ Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa, pp. 472-3

- ^ Antonicelli, Franco. Trent’anni di storia italiana 1915 – 1945, p. 79.

- ^ Antonicelli, Franco. Trent’anni di storia italiana 1915 – 1945, p. 133.

- ^ Del Boca, Angelo. Italiani in Africa Orientale: La conquista dell’Impero, p.131.

- ^1940 Article on the special road Addis Abeba-Assab and map (in Italian)

- ^Italian emigration in Etiopia (in Italian)

- ^ Semere Haile The Origins and Demise of the Ethiopia-Eritrea Federation Issue: A Journal of Opinion, Vol. 15, 1987 (1987), pp. 9-17

- ^ Paul B. Henze, Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia (New York: Palgrave, 2000), p. 282.

- ^ Thomas P. Ofcansky and LaVerle Berry, ed. (1991). A Country Study: Ethiopia (4th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN0-8444-0739-9.

- ^ Martin Meredith, The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence (Public Affairs Publishing: New York, 2005) p. 217.

- ^ ab Martin Meredith, The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence, p. 244.

- ^ Martin Meredith, The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence, p. 245.

- ^ Martin Meredith, The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence, p. 245-246.

- ^ Martin Meredith, The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence, p. 246.

- ^ Martin Meredith, The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence, p. 247.

- ^ Stéphane Courtois, ed. (1997). The Black Book of Communism. Harvard University Press. pp. 687–695. ISBN978-0-674-07608-2.

- ^“Mengistu found guilty of genocide”. BBC News. December 12, 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^“U.S. trainers prepare Ethiopians to fight”. Stars and Stripes. 2006-12-30. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- ^“Somali joy as Ethiopians withdraw”. BBC News. January 13, 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

Prehistory

East Africa, and more specifically the general area of Ethiopia, is widely considered the site of the emergence of early Homo sapiens in the Middle Paleolithic 400,000 years ago. Homo sapiens idaltu, found at site Middle Awash in Ethiopia, lived about 160,000 years ago.[26]

[edit]Antiquity

Coins of the Axumite king Endybis, 227–235 AD. British Museum. The left one reads in Greek “AΧWMITW BACIΛEYC”, “King of Axum”. The right one reads in Greek: ΕΝΔΥΒΙC ΒΑCΙΛΕΥC, “King Endybis”.

Around the 8th century BC, a kingdom known as Dʿmt was established in northern Ethiopia and Eritrea. Its capital was around the current town of Yeha, situated in northern Ethiopia. Most modern historians consider this civilization to be a native African one, although Sabaean-influenced because of the latter’s hegemony of the Red Sea,[11] while others view Dʿmt as the result of a mixture of Sabaeans of southern Arabia and indigenous peoples. However, Ge’ez, the ancient Semitic language of Ethiopia, is now thought not to have derived from Sabaean (also South Semitic). There is evidence of a Semitic-speaking presence in Ethiopia and Eritrea at least as early as 2000 BC.[27][28] Sabaean influence is now thought to have been minor, limited to a few localities, and disappearing after a few decades or a century, perhaps representing a trading or military colony in some sort of symbiosis or military alliance with the Ethiopian civilization of Dʿmt or some other proto-Aksumite state.[29]

After the fall of Dʿmt in the 4th century BC, the plateau came to be dominated by smaller successor kingdoms. In the first century AD the Aksumite Empire emerged in what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, at times extending its rule into Yemen on the other side of the Red Sea.[30] The Persian religious figure Mani listed Aksum with Rome, Persia, and China as one of the four great powers of his time.[31]

In 316 AD, a Christian philosopher from Tyre, Meropius, embarked on a voyage of exploration along the coast of Africa. He was accompanied by, among others, two Syro-Greeks, Frumentius and his brother Aedesius. The vessel was stranded on the coast, and the natives killed all the travelers except the two brothers, who were taken to the court and given positions of trust by the monarch. They both practiced the Christian faith in private, and soon converted the queen and several other members of the royal court.

[edit]Middle Ages

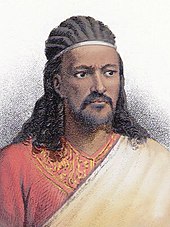

Lebna Dengel, nəgusä nägäst(Emperor) of Ethiopia and a member of the Solomonic dynasty.

The Zagwe dynasty ruled many parts of modern Ethiopia and Eritrea from approximately 1137 to 1270. The name of the dynasty is derived from the Cushitic-speaking Agaw of northern Ethiopia. From 1270 AD onwards for many centuries, the Solomonic dynasty ruled the Ethiopian Empire.

In the early 15th century, Ethiopia sought to make diplomatic contact with European kingdoms for the first time since Aksumite times. A letter from King Henry IV of England to the Emperor of Abyssinia survives.[32] In 1428, the Emperor Yeshaq sent two emissaries to Alfonso V of Aragon, who sent return emissaries who failed to complete the return trip.[33] The first continuous relations with a European country began in 1508 with Portugal under Emperor Lebna Dengel, who had just inherited the throne from his father.[34]

This proved to be an important development, for when the Empire was subjected to the attacks of the Adal General and Imam, Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi (called “Grañ“, or “the Left-handed”), Portugal assisted the Ethiopian emperor by sending weapons and four hundred men, who helped his son Gelawdewos defeat Ahmad and re-establish his rule.[35] This Ethiopian–Adal War was also one of the first proxy wars in the region as the Ottoman Empire andPortugal took sides in the conflict.

When Emperor Susenyos I converted to Roman Catholicism in 1624, years of revolt and civil unrest followed resulting in thousands of deaths.[36] The Jesuit missionaries had offended the Orthodox faith of the local Ethiopians, and on 25 June 1632 Susenyos’s son, Emperor Fasilides, declared the state religion to again be Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, and expelled the Jesuit missionaries and other Europeans.[37][38]

[edit]Aussa Sultanate

State flag of the Aussa Sultanate.

The Aussa Sultanate or Afar Sultanate succeeded the earlier Imamate of Aussa. The latter polity had come into existence in 1577, when Muhammed Jasamoved his capital from Harar to Aussa with the split of the Adal Sultanate into Aussa and the Harari city-state. At some point after 1672, Aussa declined and temporarily came to an end in conjunction with Imam Umar Din bin Adam‘s recorded ascension to the throne.[39]

The Sultanate was subsequently re-established by Kedafu around the year 1734, and was thereafter ruled by his Mudaito Dynasty.[40] The primary symbol of the Sultan was a silver baton, which was considered to have magical properties.[41]

[edit]Zemene Mesafint

Emperor Yohannes IV led Ethiopian troops in the Battle of Gundet, among other campaigns.

Between 1755 to 1855, Ethiopia experienced a period of isolation referred to as the Zemene Mesafint or “Age of Princes”. The Emperors became figureheads, controlled by warlords like Ras Mikael Sehul of Tigray, Ras Wolde Selassie of Tigray, and by the Oromo Yejju dynasty, such as Ras Gugsa of Begemder, which later led to 17th century Oromo rule of Gondar, changing the language of the court from Amharic to Afaan Oromo.[42][43]

Emperor Tewodros II‘s rule is often placed as the beginning of modern Ethiopia, ending the decentralized Zemene Mesafint(Era of the Princes).

Ethiopian isolationism ended following a British mission that concluded an alliance between the two nations; however, it was not until 1855 that Ethiopia was completely united and the power in the Emperor restored, beginning with the reign of Emperor Tewodros II. Upon his ascent, despite still large centrifugal forces, he began modernizing Ethiopia and recentralizing power in the Emperor, and Ethiopia began to take part in world affairs once again.

But Tewodros suffered several rebellions inside his empire. Northern Oromo militias, Tigrayan rebellion and the constant incursion of Ottoman Empire and Egyptian forces near the Red Sea brought the weakening and the final downfall of Emperor Tewodros II, who committed suicide in 1868 after his last battle with a British expeditionary force.

After Tewodros’ death, Tekle Giyorgis II was proclaimed Emperor. However, he was later defeated in the Battles of Zulawu (21 June 1871) and Adua (11 July 1871) by Dejazmach Kassai with the aid of John Kirkham, a British advisor who had trained his troops with modern weapons. Tekle Giyorgis was captured and deposed and Kassai was declared Emperor Yohannes IV on 21 January 1872. In 1875 and 1876, Turkish/Egyptian forces, accompanied by many European and American ‘advisors’, twice invaded Abyssinia but were initially defeated at the Battle of Gundetlosing 800 men, and then following the second invasion, decisively defeated by Emperor Yohannes IV at the Battle of Gura on 7 March 1875, losing at least 3000 killed or captured.[44] From 1885 to 1889 Ethiopia joined the Mahdist Warallied to Britain, Turkey and Egypt against the Sudanese Mahdist State. On 10 March 1889 Yonannes IV was killed whilst leading his army in the Battle of Gallabat (also called Battle of Metemma).

[edit]From Menelik to Adwa

Ethiopia as we currently know it began under the reign of Menelik II who was Emperor from 1889 until his death in 1913. From the central province of Shoa, Menelik set off to subjugate and incorporate ‘the lands and people of the South, East and West into an empire’;[45] the people subjugated and incorporated were the Oromo, Sidama, Gurage, Wolayta and other groups.[46] He did this with the help of Ras Gobena‘s Shewan Oromo militia, began expanding his kingdom to the south and east, expanding into areas that had not been held since the invasion of Ahmed Gragn, and other areas that had never been under his rule, resulting in the borders of Ethiopia of today.[47] At the same time there were also advances in road construction, electricity and education, development of a central taxation system, and the foundation and building of the city of Addis Ababa – which became capital of Shoa province in 1881 which Menelik then ruled as Ras, and subsequently became the new capital of Abyssinia on his accession to the throne in 1889. Menelik had signed the Treaty of Wichale with Italy in May 1889 in which Italy would recognize Ethiopia’s sovereignty so long as Italy could control a small area north of Ethiopia (part of modern Eritrea). In return Italy was to provide Menelik with arms and support him as emperor. The Italians used the time between the signing of the treaty and its ratification by the Italian government to further expand their territorial claims. This conflict erupted in the battle of Adwa on 1 March 1896 in which Italy’s colonial forces were defeated by the Ethiopians.[46][48]

The Great Ethiopian Famine of 1888 to 1892 cost it roughly one-third of its population.[49][50]

[edit]Haile Selassie era

Haile Selassie was crowned 2 November 1930 with the titles King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Elect of God and Power of the Trinity. He is seen by theRastafari as Jah incarnate.

The early 20th century was marked by the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie I, who came to power after Iyasu V was deposed. It was he who undertook the modernization of Ethiopia, from 1916, when he was made a Ras and Regent (Inderase) forZewditu I and became the de facto ruler of the Ethiopian Empire. Following Zewditu’s death he was made Emperor on 2 November 1930.

Haile Selassie was born from parents of three Ethiopian ethnicities: the Oromo and Amhara, which are the country’s two main ethnic groups, as well as the Gurage.

The independence of Ethiopia was interrupted by the Second Italo-Abyssinian War and Italian occupation (1936–1941).[51]During this time of attack, Haile Selassie appealed to the League of Nations in 1935, delivering an address that made him a worldwide figure, and the 1935 Time magazine Man of the Year.[52] Following the entry of Italy into World War II, British Empire forces, together with patriot Ethiopian fighters, officially liberated Ethiopia in the course of the East African Campaign in 1941, while an Italian guerrilla campaign continued until 1943. This was followed by British recognition of full sovereignty, (i.e. without any special British privileges), with the signing of theAnglo-Ethiopian Agreement in December 1944.[53] On 26 August 1942 Haile Selassie I issued a proclamation outlawing slavery.[54][55] Ethiopia had between two and four million slaves in early 20th century out of a total population of about eleven million.[56]

In 1952 Haile Selassie orchestrated the federation with Eritrea which he dissolved in 1962. This annexation sparked the Eritrean War of Independence. Although Haile Selassie was seen as a national hero, opinion within Ethiopia turned against him owing to the worldwide oil crisis of 1973, food shortages, uncertainty regarding the succession, border wars, and discontent in the middle class created through modernization.[57]

He played a leading role in the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963.

Haile Selassie’s reign came to an end in 1974, when a Soviet-backed Marxist-Leninist military junta, the “Derg” led by Mengistu Haile Mariam, deposed him, and established a one-party communist state which was called People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

[edit]Mengistu era

The ensuing regime suffered several coups, uprisings, wide-scale drought, and a huge refugee problem. In 1977, there was the Ogaden War, when Somalia captured part of the Ogaden region, but Ethiopia was able to recapture the Ogaden after receiving military aid from the USSR, Cuba, South Yemen, East Germany[58] and North Korea, including around 15,000 Cuban combat troops.

Logo of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP).

Hundreds of thousands were killed as a result of the Red Terror, forced deportations, or from the use of hunger as a weapon under Mengistu’s rule.[57]The Red Terror was carried out in response to what the government termed “White Terror”, supposedly a chain of violent events, assassinations and killings carried out by the opposition.[59] In 2006, after a trial that lasted 12 years, Ethiopia’s Federal High Court in Addis Ababa found Mengistu guilty in absentia of genocide.[60]

In the beginning of 1980s, a series of famines hit Ethiopia that affected around 8 million people, leaving 1 million dead. Insurrections against Communist rule sprang up particularly in the northern regions of Tigray and Eritrea. In 1989, the Tigrayan Peoples’ Liberation Front (TPLF) merged with other ethnically based opposition movements to form the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). Concurrently the Soviet Union began to retreat from building world communism under Mikhail Gorbachev‘s glasnost and perestroika policies, marking a dramatic reduction in aid to Ethiopia from Socialist Bloc countries. This resulted in even more economic hardship and the collapse of the military in the face of determined onslaughts by guerrilla forces in the north. The collapse of communism in general, and in Eastern Europe during the Revolutions of 1989, coincided with the Soviet Union stopping aid to Ethiopia altogether in 1990. The strategic outlook for Mengistu quickly deteriorated.

In May 1991, EPRDF forces advanced on Addis Ababa and the Soviet Union did not intervene to save the government side. Mengistu fled the country to asylum in Zimbabwe, where he still resides. The Transitional Government of Ethiopia, composed of an 87-member Council of Representatives and guided by a national charter that functioned as a transitional constitution, was set up. In June 1992, the Oromo Liberation Front withdrew from the government; in March 1993, members of the Southern Ethiopia Peoples’ Democratic Coalition also left the government. In 1994, a new constitution was written that formed a bicameral legislature and a judicial system. The first formally multi-party election took place in May 1995 in which Meles Zenawiwas elected the Prime Minister and Negasso Gidada was elected President.

[edit]Meles era

Prime Minister of Ethiopia Meles Zenawi in July, 2008

In 1994, a constitution was adopted that led to Ethiopia’s first multiparty election the following year. In May 1998, a border dispute with Eritrea led to theEritrean–Ethiopian War, which lasted until June 2000 and cost both countries an estimated $1 million a day.[61] This hurt Ethiopia’s economy, but strengthened the ruling coalition.

On 15 May 2005, Ethiopia held a third multiparty election, which was highly disputed, with some opposition groups claiming fraud. Though the Carter Center approved the pre-election conditions, it expressed its dissatisfaction with post-election matters. European Union election observers continued to accuse the ruling party of vote rigging. The opposition parties gained more than 200 parliamentary seats, compared with just 12 in the 2000 elections. Despite most opposition representatives joining the parliament, certain leaders of the CUD party, some of which refused to take up their parliamentary seats, were accused of inciting the post-election violence that ensued and were imprisoned. Amnesty International considered them “prisoners of conscience” and they were subsequently released.

The coalition of opposition parties and some individuals that was established in 2009 to oust at the general election in 2010 the regime of the EPRDF, Meles Zenawi’s party that has been in power since 1991, published its 65-page manifesto in Addis Ababa on 10 October 2009.

Some of the eight member parties of this Ethiopian Forum for Democratic Dialogue (FDD or Medrek in Amharic) include the Oromo Federalist Congress(organized by the Oromo Federalist Democratic Movement and the Oromo People’s Congress), the Arena Tigray (organized by former members of the ruling party TPLF), the Unity for Democracy and Justice (UDJ, whose leader is imprisoned), and the Coalition of Somali Democratic Forces.